Note: This article was originally written for NuCypher.

Fully homomorphic encryption is a fabled technology (at least in the cryptography community) that allows for arbitrary computation over encrypted data. With privacy as a major focus across tech, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) fits perfectly into this new narrative. FHE is relevant to public distributed ledgers (such as blockchain) and machine learning.

The first FHE scheme was successfully created in 2009 by Craig Gentry. Since then, there have been numerous proposed FHE schemes and a dearth of related work in the space. However, there’s little explanation as to why all this work is being done or the motivation for any of it. When I first started learning about FHE, I had many questions: Why are there so many schemes? Is FHE being used in any major application right now? If FHE is as powerful as described, why hasn’t it taken off yet?

We’ll start by providing an introduction to how FHE works and some areas in which it might be useful. The meat of the article is in the 2nd section where we consider why FHE has yet to have received widespread attention and some potential solutions to these issues. The TL;DR of it is that there is a complete lack of usability when working with FHE libraries currently. All of the inner workings and complexities of the FHE scheme—of which there are many—is exposed to the engineer.

Finally, we’ll link to some FHE libraries if you’re interested in getting your hands dirty.

- What is fully homomorphic encryption?

- Why FHE hasn’t taken off yet

- What’s the takeaway from all of this?

- Show me the code!

What is fully homomorphic encryption?

Fully homomorphic encryption is a type of encryption scheme that allows you to perform arbitrary* computations on encrypted data.

* Not completely true but we’ll leave that out for now

A Refresher on Public Key Encryption Schemes

Let’s start with a brief review of encryption schemes. Plaintext is data in the clear (i.e. unencrypted data) whereas ciphertext is encrypted data.

Algorithms in an Encryption Scheme

An encryption scheme includes the following 3 algorithms:

KeyGen(...security_parameters)→keys: The Key Generation algorithm takes some security parameter(s) as its input. It then outputs the key(s) of the scheme.Encrypt(plaintext, key, randomness)→ciphertext: The Encryption algorithm take a plaintext, a key, and some randomness (encryption must be probabilitistic to be “secure”) as inputs. It then outputs the corresponding ciphertext (i.e. encrypted data).Decrypt(ciphertext, key)→plaintext: The Decryption algorithm takes a ciphertext and a key as inputs. It outputs the corresponding plaintext.

In a private key encryption scheme, the same key is used to both encrypt and decrypt. That means anyone who can encrypt plaintext (i.e. data in the clear) can also decrypt ciphertext (i.e. encrypted data). These types of encryption schemes are also referred to as “symmetric” since the relationship between encryption/decryption is symmetric.

However, in a public key encryption scheme, different keys are used to encrypt and decrypt. An individual may be able to encrypt data but have no way of decrypting the corresponding ciphertext. These types of encryption schemes are also referred to as “asymmetric” since the relationship between encryption/decryption is asymmetric.

You may have heard of the ElGamal encryption scheme before (which is based on the Diffie-Hellman key exchange). These schemes are usually taught in an introductory cryptography course and rely on a commonly used type of cryptography called elliptic curve cryptography.

So what’s the “homomorphic” part mean?

We will turn our focus to public key homomorphic encryption schemes as they are the most useful. The homomorphic part implies that there is a special relationship between performing computations in the plaintext space (i.e. all valid plaintexts) vs. ciphertext space (i.e. all valid ciphertexts).

Specifically, in a “homomorphic encryption scheme,” the following relationships hold:

- Homomorphic addition:

Encrypt(a) + Encrypt(b) = Encrypt(a + b) - Homomorphic multiplication:

Encrypt(a) * Encrypt(b) = Encrypt(a * b)

Allowing you to do something like:

Encrypt(3xy + x) = Encrypt(3xy) + Encrypt(x) = [3 * Encrypt(x) * Encrypt(y)] + Encrypt(x)

So just by knowing Encrypt(x) and Encrypt(y), we can compute the encryption of more complicated polynomial expressions.

How does it work? What’s the intuition?

Let Encrypt(a) be referred to as a'. Let Encrypt(b) be referred to as b'. Recall that a' and b' are ciphertexts.

Every time we perform a homomorphic operation, we add additional noise to the ciphertexts. At some point if the noise gets too big, you won’t be able to successfully decrypt the ciphertext. You’re just out of luck. For homomorphic addition, the noise doesn’t grow too badly. You can think of the noise growth as Noise(a' + b') = Noise(a') + Noise(b'). However, the problem lies with performing homomorphic multiplication. In a homomorphic multiplication, the noise growth behaves as Noise(a' * b') = Noise(a') * Noise(b').

Let’s use some numbers to make this more concrete. We’ll say that Noise(a') is 10. We’ll say that Noise(b') is 20. The FHE scheme has some noise ceiling after which point we cannot decrypt the cipherext even if we have the decryption key. For our example, let’s say the noise ceiling is 300. After performing a single homomorphic addition between the two cipherexts, the noise will be 10 + 20 = 30. Not bad! However, if we perform a single homomorphic multiplication between a' and b', the resulting noise will be 10 * 20 = 200 for the ciphertext a' * b'. If we then tried to compute (a' * b') * (a'), the noise would be too big for the FHE scheme! Thus, we would not be able to decrypt (a' * b') * (a') even if we had the decryption key (since Noise(a' * b') * Noise(a') = 200 * 10 = 2000).

It’s your job to correctly set all parameters of the scheme, perform “noise control” operations at the right time (we won’t go into what these operations are in this article since they can even differ by scheme), and try not to do too many homomorphic multiplications. Does that sound intimidating to you? You’re in good company then.

Note: There are some ways of getting around the fixed noise ceiling such as “bootstrapping.” Bootstrapping comes with its own set of complexities and trade-offs however.

What’s needed to build a fully homomorphic encryption scheme?

All FHE schemes use a specific type of post-quantum cryptography called lattice cryptography. The good news is that FHE is resistant to attacks from a quantum computer (if we should be concerned about such a thing is an entirely different topic). The bad news is you likely have no familiarity with lattice cryptography even if you’ve taken an introductory cryptography course before.

Simply put, lattices sit inside the real vector space (otherwise known as R^n) and can be represented using vectors and matrices (which you definitely should have familiarity with!).

FHE schemes can be broken down into 3 types depending on how they model computation (see this presentation if interested in more advanced technical details). The first type models computations as boolean circuits (i.e. bits). The second type models computation as modular arithmetic (i.e. “clock” arithmetic). The third and final type models computations as floating point arithmetic.

| Computational Model | Good for | Schemes* |

|---|---|---|

| Boolean | Number Comparison | TFHE |

| Modular Arithmetic | Integer Arithmetic, Scalar Multiplication | BGV, BFV |

| Floating Point Arithmetic | Polynomial Approximation, Machine Learning Models | CKKS |

The names of these schemes usually come from the last names of the authors who created it. For example, “BGV” comes from the authors Brakerski, Gentry, and Vaikuntanathan.

* Not an exhaustive list of schemes! I’ve just listed some well-known ones.

Why do we care about any of this?

Private Transactions on a Public Ledger (e.g. blockchain). A private transaction scheme allows a user to securely send digital currency to some recipient without revealing the amount being sent to anyone (apart from the intended recipient) on a public, distributed ledger. This is in contrast to cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin where transactions and balances are all public information.

We assume a (public key) fully homomorphic encryption scheme. All encryptions are done with respect to the Receiver’s keys.

- Sender wants to send

ttokens to the Receiver. Sender encryptstunder the Receiver’s public key. - Sender publishes

Encrypt(t)on the public ledger. - Notice that

Encrypt(t) + Encrypt(Receiver's balance) = Encrypt(Receiver's balance after performing the transaction).

This can be extended to more interesting financial applications such as auctions, voting, and derivatives. An FHE scheme that models computation as modular arithmetic is likely to be the most suitable for this type of application.

Note: For this to work in practice, some other cryptographic tools are also needed (such as zero-knowledge proofs).

Private Machine Learning. There’s been increased interest in the last few years around how we might be able to “learn” from data (via machine learning) while still keeping the data itself private. FHE is one tool that can help us achieve this goal. In contrast to the previous application, we likely want an FHE scheme that models computations as floating point arithmetic here.

One well-known work in this space is Crypto-Nets which combines (as the name might suggest) FHE and neural networks to allow for outsourced machine learning. When people talk about “outsourced machine learning,” the setting usually being described is one in which a data owner wants to learn about his data but does not feel comfortable openly sharing his data with some company providing machine learning models. Thus, the data owner encrypts his data using FHE and allows the machine learning company to run their models on the encrypted data set.

Homomorphic encryption is not the sole solution to this problem; differential privacy is a closely related subject that has garnered a lot of attention. Differential privacy is more statistics than cryptography as it does not directly involve encryption/decryption. It works by adding noise to data in the clear while still guaranteeing that meaningful insights can be drawn from the noisy data sets. Apple is one major company that purportedly uses differential privacy to learn about your behavior while maintaining some level of privacy.

Why FHE Hasn’t Taken off Yet: Challenges in the Space

So far this all sounds great but I’ve been leaving out a number of problems.

Many Different Schemes (aka everyone is speaking a different language)

So you’ve decided you want to use FHE, great! Here’s some considerations that now need to be taken into account:

- How do I model computation?

FHE schemes model computation in one of three ways—as boolean circuits, modular arithmetic, or floating point arithmetic. Hopefully it’s obvious which model you need since there aren’t many resources beyond introductory ones like this to help you out. This question is likely the least of your concerns though.

- What if I have multiple options for FHE schemes that fall under the same computational model I need (e.g. choosing between BGV vs. BFV for modular arithmetic)?

Hmm, that’s unfortunate. There isn’t much work explaining the tradeoffs between different schemes with the same computational model. You’ll probably have to play around with the various schemes and implement your specific use case with both of them to determine which is best. There are some very involved research papers (such as this) that you can try wading through.

- Do schemes based on different computational models otherwise behave the same?

Kind of but not really. Different schemes tend to use different techniques to control efficiency and noise growth that you’ll need to understand to successfully work with FHE. Additionally, the schemes have different parameters you need to understand in order to set them properly. The parameters affect not only the security of the scheme (which is a given in cryptography), but also the sorts of plaintexts you can work with, the number of homomorphic computations you can do, and the overall performance of the scheme.

- Are the different schemes compatible at all?

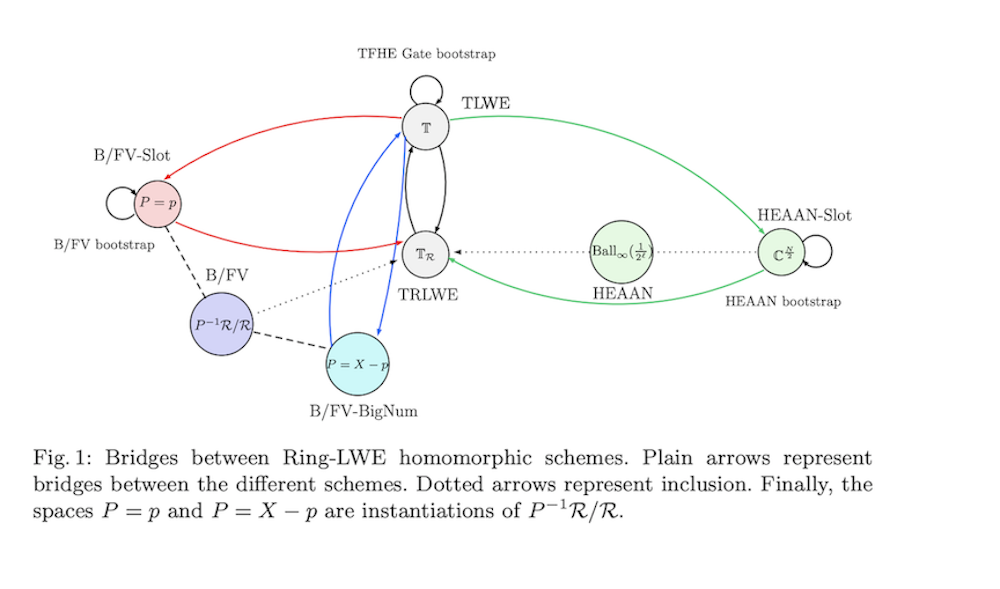

Does this picture* help?

Probably not unless you know quite a bit of math and cryptography. There is a relationship between some of the FHE schemes but to understand the relationship you also need to understand how the various FHE schemes work in detail.

Having a lot of choices is great!

But it’s not great when:

- you don’t know the tradeoffs between the different FHE schemes or how the schemes relate to one another.

- you have to invest a lot of energy into understanding a single scheme

- a lot of the knowledge gained from understanding one scheme is not really transferable to learning a new scheme (under a different computational model)

Potential Solutions:

1. Updated and improved benchmarking efforts

A large issue is the lack of up-to-date benchmarking efforts. It’s hard to recommend which FHE scheme to use for a particular use case when we don’t know how one implementation performs against another (on the same machine, for a particular set of comparable parameters). FHE libraries change quickly, incorporating new optimizations, so benchmarking efforts from 1-2 years ago quickly lose relevancy (such as this from 2018 for various implementations of the BFV scheme).

2. Better resources/guides to explain tradeoffs between schemes

Without up-to-date benchmarking of different schemes and libraries, it’s impossible to provide good resources that explain the tradeoffs between the FHE schemes in practice. There have been some presentations (such as this one) that try to illuminate the differences between the 3 computational models in FHE. However, there aren’t any good resources to help when trying to choose between different schemes using the same computational model.

3. Ability to move between different FHE schemes (i.e. interoperability)

If there were some interoperability between different FHE schemes, it would be easier to understand how the schemes relate to one another. An academic work on this topic is CHIMERA which provides a framework for switching between TFHE (boolean), BFV (modular arithmetic), and HEAAN (floating point arithmetic). Unfortunately, this work requires a very strong background in abstract algebra along with good familiarity of all the FHE schemes used. More accessible resources explaining the relationship between the different types of schemes would be nice (by “type” we mean the 3 types of computational models—boolean, modular arithmetic, floating point arithmetic.

* Image is from CHIMERA’s paper

Efficiency (more complex of an issue than it seems)

If you talk to most people familiar with FHE and ask them why FHE isn’t being used, they’ll often wave the issue off by saying something like “oh, it’s not efficient.” Personally, I find this explanation to be a bit lazy because it vastly simplifies the issue. Public key encryption is less efficient than private key encryption but that doesn’t mean everyone exclusively uses private key encryption. There are perfectly reasonable cases where a certain less efficient technology should be used.

Personal rant aside, we’re going to look at some considerations you have to take into account for efficiency with FHE.

- How many computations do you want to perform?

Some FHE schemes allow you to perform a truly arbitrary number of computations on encrypted data. Many schemes, however, only allow for a certain number of homomorphic operations to be performed. After that point, there’s no guarantee decryption will be successful. Say, for example, the FHE scheme only allows for 100 sequential homomorphic multiplications (note: addition is generally “easy” in FHE schemes, whereas multiplication is much harder). If we tried to do the 101th homomorphic multiplication, there’s no guarantee that the resulting ciphertext can be correctly decrypted. The schemes that allow for a truly arbitrary number of homomorphic computations suffer from very poor performance. If you’re able to figure out a ceiling on the number of homomorphic multiplications you need to do, that will help to achieve much better performance.

- How big do you need your plaintext space to be?

he larger the plaintext space, the slower it will be to perform operations. For FHE schemes that model computation as modular arithmetic, choosing a modulus on the order of 1000 vs. 1,000,000 makes a large difference in terms of what plaintexts you can represent. This might be especially important if you’re representing account balances with your ciphertexts and need to ensure they don’t “wrap around” the modulus.

- Are you going to perform the same operation on many different plaintexts or ciphertexts (i.e. “SIMD” style computations)?

Some FHE schemes can take advantage of “SIMD” style operations to perform the same operation on multiple plaintexts or ciphertexts simultaneously. If this sort of parallelization is useful for you, you should consider exploring schemes and libraries that offer this functionality. SIMD-style operations, if used correctly, can really improve efficiency.

- What key sizes are acceptable to you?

With TFHE, for example, some keys you’ll need to access in the scheme can be 1 GB large! The performance, in terms of timings, may be decent but you’re instead left with a giant key you need to store.

- Are you okay with large ciphertexts?

Ciphertext expansion can be quite bad when working with FHE. Looking again at TFHE, the plaintext-to-ciphertext expansion is 10,000:1 for an acceptable level of security (100 bits).

- What matters most for you in terms of performance?

You can’t “have it all” in FHE so it’s important to determine what you need vs. want. Maybe you really need fast comparison of numbers. Maybe you really need to parallelize computation. Maybe you need a large plaintext space. All these little considerations need to be taken into account when choosing an FHE scheme.

Potential Solutions:

1. Hardware acceleration

Some FHE schemes can be accelerated using GPUs; examples of such libraries include nuFHE and cuFHE. Other efforts to accelerate FHE schemes have included using FPGAs (e.g. HEEAX). HEEAX works with the CKKS scheme (floating point arithmetic) and can yield performance speed-ups of anywhere from 12x to over 250x depending on the specific operation. Unfortunately, the paper suggests that a FPGA-based approach is not as successful for the BFV scheme (integer arithmetic).

2. Research breakthroughs improving FHE schemes

Easier said than done of course.

Usability (there is none)

The previous discussion leads us to our final point—usability. FHE is not beginner-friendly, not user-friendly, and certainly not non-cryptographer-friendly. There really isn’t any usability for an engineer lacking a math or cryptography background.

Most FHE libraries require deep expertise of the underlying cryptographic scheme to use both correctly and efficiently. Another cryptographer has described working with FHE as similar to writing assembly— there’s a huge difference in performance between good and great implementations. Wading through libraries like HElib can be intimidating without a strong background in the underlying scheme.

Is the situation really that bad?

We’ll briefly touch on the issues that make FHE exceptionally user-unfriendly.

- Parameter setup is non-trivial. For example, in BFV (which is simpler than the BGV scheme), we have to set up a polynomial modulus, a coefficient modulus, and a plaintext modulus. Setting these parameters requires understanding how they affect the scheme (e.g. what sort of operations you’re planning on doing, how many operations). Additionally, to understand what the parameters mean, you’ll have to learn some basic theory about rings (abstract algebra). We currently cannot abstract away these issues; it’s just necessary for working with FHE schemes.

- Public key encryption has just 3 main algorithms (

KeyGen,Encrypt,Derypt), but it’s not so simple for FHE schemes which have additional operations (that also differ between schemes). Because you need to understand how and when to use certain operations, working with FHE requires developing intuition yourself. - To develop good intuition, you need to work with the scheme….but some libraries have very little documentation.

- Understanding one type of scheme may not transfer very well to understanding a different type of scheme (by type here, I’m referring to the three different computational models).

Potential Solutions:

1. Standardization efforts

By this, we mean standards to make it clear what parameters to use, what functionalities are offered, etc.

Standardization efforts are currently led by the open industry/government/academic consortium “Homomorphic Encryption Standardization.” They’ve already released draft proposals around security and API standards for homomorphic encryption. They tend to meet 1-2x a year if you’re interested in attending their meetings.

2. More user-friendly libraries and examples

One example of this is Microsoft’s SEAL which has an incredibly instructive examples section. Hopefully more libraries will take the time to create user-friendly documentation and examples.

3. Potential compilers

There have been discussions in the FHE community for awhile now about creating a compiler or some intermediate representation to make FHE easier to work with. Cingulata is one such attempt.

What’s the takeaway from all of this?

“It’s not you, it’s FHE.”

You know that cliche breakup line “it’s not you, it’s me?” Well, that’s particularly true here.

High-level programming languages have helped to abstract away a lot of the complexity of how your computer works. But there is no analogue of “high-level programming languages” when working with FHE. You can’t abstract away any of the complexities (of which there are a lot). Although standardization is ongoing and there are efforts to make FHE more beginner-friendly, FHE just isn’t ready to be used by non-cryptographers at the moment in a production-ready environment.

Show me the code!

If you do not have previous experience with FHE, we recommend starting with a more user-friendly library such as SEAL.

Some libraries (such as SEAL and PALISADE) offer multiple types of FHE schemes. To prevent confusion, we list the specific FHE scheme in paratheses after the library’s name.

| Computational Model | Available Libraries |

|---|---|

| Boolean | TFHE, nuFHE, PALISADE(tFHE) |

| Modular Arithmetic | HElib, SEAL(BFV), Lattigo(BFV), PALISADE(BFV, BGV) |

| Floating Point Arithmetic | SEAL(CKKS), Lattigo(CKKS), PALISADE(CKKS) |